Sept. 20 — The oil and natural gas industry in Colorado was losing the public relations game.

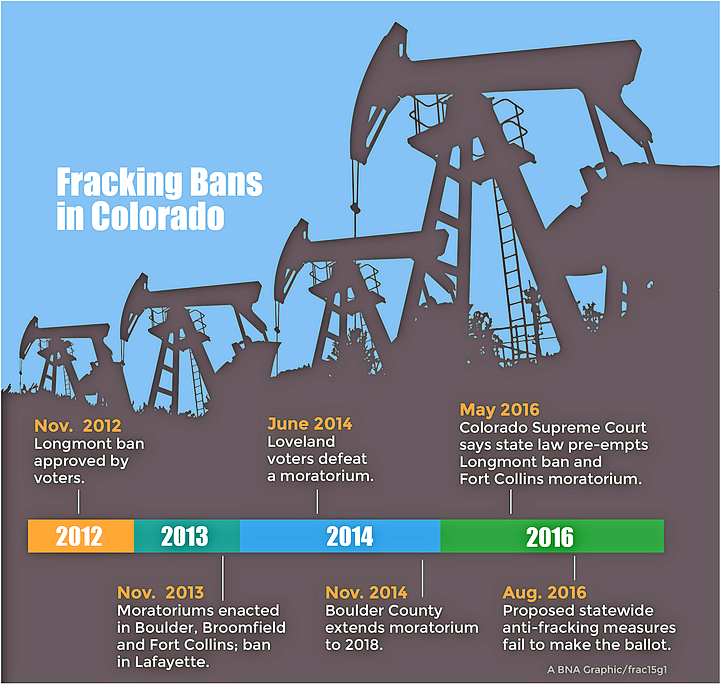

One industry association executive said it was “caught flat-footed” as oil and gas companies watched voters in Longmont pass a ban on fracking and other drilling activities in November 2012. A year later, voters approved four more citizen initiatives, imposing fracking moratoriums in Boulder County, Broomfield and Fort Collins and a permanent ban in Lafayette.

Oil and gas producers knew it was time to respond. They quickly invested in the creation of new issue committees and information campaigns designed to beat back bans. They stressed the importance of energy exploration and production to the state economy.

Meanwhile, environmentalists and community activists accused the industry of rigging the political process, creating “disinformation” campaigns and even harassing volunteers who were out in public gathering signatures in support of the proposed drilling restrictions.

Industry groups outspent them by a 15-to-1 ratio, paying freelancers to write paid newspaper commentaries and flooding radio and TV outlets with pro-industry messages, environmental advocates said.

In the 2016 election cycle, one of the new issue groups, Protecting Colorado’s Economy, Environment, and Energy Independence, launched a counter-campaign urging voters to “Decline to Sign” petitions in support of two proposed anti-fracking ballot measures it described as “job-killing” and “too extreme” for the state.

The strategy worked. At the end of August, Colorado Secretary of State Wayne Williams (R) announced that the campaigns behind the two measures had failed to gather enough signatures to qualify the initiatives for the ballot.

Successful Model

The successful approach taken in Colorado presents a pathway for the oil and gas industry to take in other states where fracking restrictions are being sought by statewide and local initiative campaigns, sources told Bloomberg BNA.

“There’s a lot to be gleaned” from what happened in Colorado, said Kathleen Sgamma, vice president of government and public affairs of the Western Energy Alliance, an industry group in Denver. “It demonstrates the need to designate significant resources for public outreach and education. When we see these crop up elsewhere, industry is going to be much-better prepared seeing the successful model of Colorado,” she said.

Environmentalists and community activists who promoted the two proposals, Initiatives 75 and 78, say they were outmaneuvered by industry’s disinformation effort designed to confuse voters and make them second-guess signing the petitions to put the measures on the ballot.

“They hired people to go out there and harass signature gatherers,” Micah Parkin of 350Colorado, one of the groups driving the petition campaign, told Bloomberg BNA. “They followed our petition circulators around, holding signs that said, ‘Don’t destroy Colorado’s economy’ and ‘Don’t take my job,’” she said.

Volunteers Videotaped

Parkin said she and her husband were videotaped by three men while collecting voters’ signatures in downtown Denver. “It’s an alarming thing when they are videoing you and you don’t know who these people are.”

When she and her husband confronted the cameramen, they said they “had been paid by oil and gas” to take photographs and videos of petition gatherers, but they had no other comment, she said.

“It was an uncomfortable thing. Other volunteer signature gatherers faced similar harassment, which made their jobs much harder,” she said. “Petition gathering is an exercise of free speech. It’s supposed to be protected” by the First Amendment, she said.

Karen Crummy, communications director for Protecting Colorado’s Economy, Environment, and Energy Independence, or Protect Colorado for short, told Bloomberg BNA her organization didn’t direct its members or associates to videotape signature gatherers. “Never once did we advise or want anyone to harass signature gatherers,” she said. The intent of Protect Colorado’s “Decline to Sign” campaign was to make sure voters knew what they were agreeing to, she said.

The American Petroleum Institute and its member companies “have not and will not ever participate in an activity that denies someone their rights as a voter,” Tracee Bentley, executive director of the Colorado Petroleum Council, a division of the API, told Bloomberg BNA. The industry argument prevailed, she said, because “we told people ‘Here’s what you should know: Fracking is safe, air and water are going to be safe, and Colorado has the safest rules and regs in the country.”

Difficulty Gathering Signatures

But in the face of industry’s unprecedented $15 million anti-signature campaign, voters were intimidated, and signature gathering was suppressed, Suzanne Spiegel of Frack Free Colorado, said in a statement. Supporters of the ballot measure had difficulty raising enough signatures for the initiatives, although recent polls showed 57 percent of state residents supported Initiative 78, which would have increased setbacks, the minimum distances between wells and occupied buildings such as homes, schools and hospitals, from the current 500 feet to 2,500 feet.

Spiegel said the supporters of Initiatives 75 and 78 will be back. “The actions of the industry have only served to galvanize supporters, and we intend to fight the destructive and dangerous fracking practices that harm our health and destroy our environment.”

Initiative 75 would have given local governments the authority to regulate and even ban fracking. Initiative 78 would have made more than 90 percent of the state off limits to new drilling. Industry viewed both measures as de facto bans on their operations.

Colorado was “a big test case” for proposals restricting fracking, Sgamma said. “We won a big battle here, because if they had gotten on the ballot and the voters had voted for them, we would have seen these types of initiatives in other states—Utah, Wyoming, Texas,” she said.

‘Turned a Corner.’

“We’re not going to assume this is going to go away,” she said, “but the spectacular failure” of the Colorado proposals to get on the ballot could mean the industry “has turned a corner” on these kinds of citizen efforts.

“I do think wiser heads are prevailing,” she said. “The American public in general has understood over the last few years that fracking is not this scary, unregulated process that radical environmental groups would have you believe. The responsible development of oil and natural gas has broad support across the political spectrum.”

In the state ballot wars, the anti-fracking forces struck first. Longmont became the first city in Colorado to enact a ban with a voter-approved ballot measure in November 2012.

At about the same time, the Natural Resources Defense Council, hearing from members across the country who were increasingly concerned about drilling in their localities, launched the Community Fracking Defense Project with the goal of offering legal and policy aid to communities “seeking protection from industrial gas drilling.”

Assisting Communities

The intent of the project “is to assist communities that want to establish ordinances that protect their environment and quality of life from the risk of fracking,” Amy Mall, senior policy analyst at the NRDC, told Bloomberg BNA. “Communities are trying to step in where states and the federal government have not done enough to protect clean air and water. They are trying to protect their citizens’ way of life, and we think communities should have the right to say no.”

A similar “community rights” movement was being advanced by the Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund, a public-interest law firm in Ohio that was helping cities and towns address “key barriers to local self-governance.” The group encouraged municipalities to pass a “Community Bill of Rights” giving local governments the authority to control all sorts of industrial activities—including fracking—within their jurisdictions. Lafayette, Colo., passed such a “bill of rights” in November 2013 on the same ballot that voters in Boulder, Broomfield and Fort Collins approved fracking moratoriums. The anti-fracking movement in the state was scoring victory after victory.

The 2012 and 2013 elections “caught us flat-footed,” Dan Haley, president and chief executive officer of the Colorado Oil and Gas Association, said during a presentation at its annual meeting in August. The industry’s right to operate in the state had always been assured by the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Act, but oil and natural gas companies were unaccustomed to fighting skirmishes at the local level.

The association sued Longmont and Fort Collins and ultimately prevailed in May 2016 when the Colorado Supreme Court ruled the state law preempts local fracking restrictions City of Fort Collins v. Colo. Oil and Gas Ass’n , Colo., No. 15SC668, 5/2/16 , City of Longmont v. Colo. Oil and Gas Ass’n , Colo., No. 15SC667, 5/2/16 . But Haley and others knew something had to be done to slow the advance of these citizens’ initiatives.

Other State Campaigns

Similar campaigns were moving in other states. In March 2014, the Denton Drilling Awareness Network and Earthworks initiated a push to get the City Council in Denton, Texas, a city of 120,000 people near Fort Worth, to ban fracking. When the effort failed in July, they turned to the ballot, winning approval with 59 percent of the vote.

At the time, Denton—known as the birthplace of fracking—had 270 active gas wells, some of them within 200 feet of homes. Less than 24 hours after polls closed, oil and gas producers sued to nullify the ban, ultimately winning in court Texas Oil and Gas Ass’n v. City of Denton , Tex. Dist. Ct., No. 14-08933-431, 11/5/15 . The industry then lobbied the Texas Legislature to approve a law prohibiting local fracking bans.

In June 2016, supporters of a proposed fracking ban in Michigan announced that although they had gathered more than 207,000 signatures in support of the measure, it wasn’t enough to get on the November ballot. They also sued election officials in state court on the constitutionality of restrictions on the signature-gathering time period. A judge dismissed the case in August, saying the plaintiffs didn't have standing Committee to Ban Fracking in Michigan v. Thomas, Mich. Ct. Cl., No. 16-000122-MM, Summary Disposition 8/8/16 .

The plaintiffs in the case, the Committee to Ban Fracking in Michigan, say the oil and gas industry is behind recent actions taken by the state Legislature to confine the petition circulation period to a strict 180 days, in an effort targeted to stop the committee. The legislation (S.B. 776) passed both the Senate and the House and awaits action by the governor, the committee said.

Ohio Dispute

Residents of three counties in Ohio—Athens, Meigs, and Portage—filed a lawsuit in August alleging the secretary of state there illegally blocked from the November ballot citizen-sponsored charter initiatives proposed in part to “protect people and the environment from the harms associated with oil and gas drilling projects,” the Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund said. Several industry groups—including the petroleum institute and the Ohio Oil and Gas Association—filed briefs with the court supporting the secretary of state’s decision to disallow the measures of the ballot.

“The gameplan with these extreme fractivist groups is to start small, ban fracking and put on moratoriums at the local level, then go statewide,” Crummy said. “It’s easier to get on the ballot in Colorado than in a lot of states, and we have this kind of libertarian, purple-state way about us. What happened here could be something for others to look at, but it isn’t a one-size-fits-all thing.”

Industry has faced a backlash for the amount of money it has spent fighting ballot measures, Crummy acknowledged. According to Sept. 6 filings with the Colorado secretary of state, Protect Colorado had received $13,407,184 in monetary contributions and spent $7,146,411 from the start of the year through Aug. 31. The Yes for Health & Safety Over Fracking campaign, the funding organization for the anti-fracking initiatives, had received $526,202 and spent $451,499 in the same time period. The industry group spent 15 times what the anti-fracking campaign spent and raised 25 times as much.

“Scaring people is cheap. Giving them the facts and accurate information is really expensive,” Crummy said. “The gist is, what we’ve learned from all this is you can’t just think the public knows what fracking is, or understand oil and gas development. The more we talk about it, the more people say, ‘I get it.’”

Not PR Types

“This is a very practical industry run by engineers and geologists,” Sgamma said. “They are not PR types; they don’t want to engage in that. They want to go out, find oil and gas and do it in the most environmentally responsible way possible. But when faced with an existential threat, they said, ‘You know what ... we do need to educate the public.’ And that’s when companies started stepping up to the plate and putting the dollars behind the public education that’s necessary.”

In the midst of the 2013 election cycle, as four more anti-fracking measures loomed in Colorado, Anadarko Petroleum Corp. and Noble Energy formed Coloradans for Responsible Energy Development with the aim of educating voters about the safety of fracking and the benefits of the industry to the state.

The failure of Initiatives 75 and 78 demonstrates state residents “recognize the strong regulatory structure already in place and the disastrous impacts these measures would’ve had on our state,” Robin Olsen, spokeswoman for Anadarko, told Bloomberg BNA. “This is good news for all Colorado businesses and a victory for the state’s economy.”

Supporting Coloradans for Responsible Energy Development and Protect Colorado was another coalition, “Vital for Colorado,” formed in March 2014 and including representatives of several industries, chambers of commerce, business advocacy groups and elected officials in the state.

Business Groups Rose Up

“What we saw in Colorado was a lot of local businesses rise up as they have in the past to talk about these issues and show the importance of the industry, and what these proposals really are, which was to effectively ban oil and natural gas development,” Reid Porter, spokesman for the API, told Bloomberg BNA.

API’s Bentley said given the industry’s recent success in Colorado, she is fielding questions from industry organizations outside the state about the campaign. “They want to know what our messaging was and who our targets were and how did we use it with the new folks who have moved to Colorado.” Most of the inquiries come from oil and gas producers facing initiatives at the local, as opposed to the state, level, she said.

Despite the defeat in Colorado, environmentalists and community groups across the country will continue to pursue ballot measures to restrict drilling.

“For legal and technical reasons, the communities in Colorado may not have achieved everything they set out to do, but that doesn’t mean people are less concerned about the health of their children and their community,” Mall said. “Community efforts are not going away.”

Said Parkin: “We are going to keep trying. We’re going to keep attacking it from every angle possible.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Tripp Baltz in Denver at [email protected]

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Larry Pearl at [email protected]

Copyright © 2016 The Bureau of National Affairs, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

Click here to view original web page at www.bna.com