The common man does not give much thought to the signature on the currency notes in his wallet. He couldn't care less about the existence of the central bank itself, as he has little context to it beyond the coins and the notes. So, barring a few people who have some interest in the economy, a large proportion of the country's population wouldn't be aware of the Reserve Bank of India's (RBI) governor.

However, when the central bank governor was Raghuram Rajan, the smart guy who predicted the global credit crisis three years before it actually happened, everyone had to take note. After all, the common man was still suffering from the repercussions of the once-in-a-century credit crisis, having lost his job or at the least, seeing his pay hikes getting stuck whereas prices didn't.

This public interest on matters considered arcane is what Rajan brought to the grey world of central banking - making RBI and its functions more mainstream. People may still find it difficult to understand repo and reverse repo, or may use fiscal policy and monetary policy interchangeably, but they have now some idea on why inflation is a silent killer and that it might not be a very good idea to see the rupee's value getting at par with the dollar for the sake of our exporters. No wonder then that Rajan's departure saw social media going crazy, as people bereaved the departure of their beloved public intellectual. Followers of Rajan's critics rejoiced his departure, hoping the country would now prosper under a softer governor who would cut rates and lead the country to a path of 10 per cent annual growth.

As Rajan demits office this Sunday after three years at the helm of RBI, the legend of Raghuram Rajan will be hard to emulate by many a public figure in the future. What he did in his role as a governor was no doubt stellar but perhaps no different than what was expected of an RBI governor.

C Rangarajan oversaw economic liberalisation, Bimal Jalan guided the country from a dangerous Asian financial crisis, Y V Reddy had the foresight to ring-fence Indian banks from getting into dangerous derivatives that sank global giants, and D Subbarao steered India's financial system through those dangerous and uncertain years of global credit crisis. Rajan, as expected, furthered his predecessors' agenda and continued with the same resolution to make India's financial system safer, and direct the economy towards further liberalisation.

Rajan also spoke on a wide range of issues that went beyond pure economics. The verdict on his tenure is that it has been a great success, but there are critics, not to mention some that went overboard in attacking his personality rather than his work. For most neutral observers, his regime was the one that built the RBI's credibility at a time when all other central banks globally were fighting to preserve theirs.

"The battle we are really fighting today is for credibility. Credibility that at the first sign of trouble, we don't abandon our policy regime, that we stick to it. Once we gain the credibility, even if the economy is hit by shocks, you won't have a significant movement in flows in and out or a significant change in inflation," he told reporters at an interaction. The war on credibility is yet to be won, but surely the outgoing governor managed to break the resistance.

Rajan's three-year term saw India's crony capitalists hiding in fear of meek bankers' resolve to draw blood. His deep surgery to clean up banks' balance sheets forced them to show a non-compromising attitude towards defaulters, drawing them to courts, sell assets of errant promoters, and even take over companies.

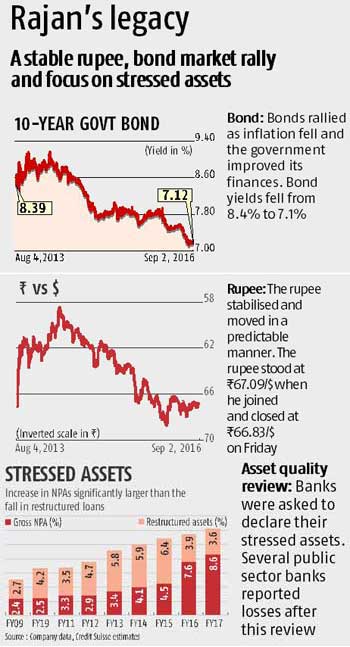

The bad debts in banks' books jumped to about Rs 6 lakh crore by March 2016, from Rs 2.28 lakh crore they reported in December 2013, the first full quarter under Rajan, as he directed the banks to hide nothing.

His name itself was credible enough for the market to arrest a rupee slide from its all-time low of Rs 68.87 a dollar a few days before he took office as governor.

RBI mobilised about $34 billion of deposits under foreign currency non resident bank deposits and tier-1 bonds for banks and the rupee entered a narrow band, only depreciating in a predictable manner every year. But Rajan did not let companies take advantage of that and forego hedging. He was quite clear that the central bank was not there to bail out companies in financial distress.

He also built a record foreign exchange reserve for the country - $366 billion plus, in addition to the positions taken in the forwards market to see FCNR (B) redemptions sail through between September and November this year. Where he failed repeatedly was to make banks pass on interest rate cuts. And, analysts do not blame banks for that. Even when the liquidity deficit hit a record Rs 2 lakh crore, Rajan insisted on pumping short-term liquidity, hoping banks will make do with it. He steadfastly refused to reason with banks that longer term liquidity would be needed for them to tide over a deficit. Banks, predictably, did not entertain Rajan with stronger rate cuts.

Only a few days before his tenure comes to an end, he announced a host of measures that would deepen the bond and currency market, which he worked closely with his successor Urjit Patel.

Those measures, which include allowing banks to raise money through masala bonds, increasing single entity exposure in the currency market, pushing firms to the corporate bond market for their borrowings, and allowing foreign investors direct access in bond trading platform - Rajan almost closed his unfinished agenda and signs off as one of the great thinkers in India's economic history.

Rajan had expressed his intention to go back to the academic world after his stint with the apex bank. His final public appearance , as the RBI governor, suitably happens to be at St. Stephen's College, New Delhi, on Saturday.

| THREE YEARS AT THE HELM |

|

Click here to view original web page at www.business-standard.com